|

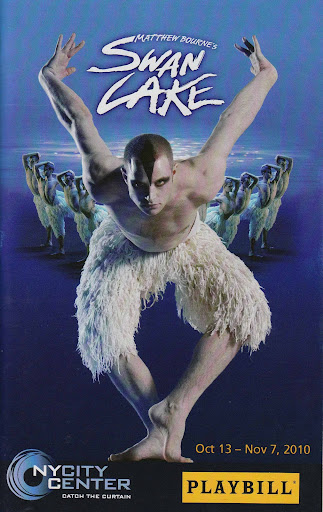

Stop whatever you're doing, drop everything, go to New York, and see Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake at the New York City Center. I heard of this production 15 years ago, when it first appeared in the UK, and then again in 1999, when it took several Tony awards on Broadway, but never had a chance to see it. As luck would have it, while I was thinking whether I should buy a ticket and go to New York, my friend Natasha who lives in the area got an email from the City Center with an offer of a discount for selected performances. We bought tickets for the Saturday, October 16th, 2 pm matinee, with an additional benefit of a post-performance talk-back with Matthew Bourne.

I knew very little about the show and didn't quite know what to expect. I read that the swans were cast as an all-male troupe but I wasn't sure if Bourne's dance company was an all-male company (it is not) or what his choreographic style was (it is modern dance). |

While the music is that of the original Tchaikovsky's ballet, the plot is totally reinvented. Two basic ideas form its foundation: (1) the main character (Prince) is someone who is trapped into living a life he loathes—life governed by duty, formality, and etiquette, who cannot be who he wants to be, who yearns for love, affection, and touch he cannot get from anyone around him, least of all from his mother, the Queen; and (2) his desire to free himself from the strictures of society and convention, to be independent, wild, and—at the same time—loved and accepted, is personified by an image of a fierce, strong, beautiful, and menacing creature—the Swan. Since the Swan is Prince's alter ego, it absolutely makes sense that swans are danced by males.

So, should this production be dismissed as “a gay Swan Lake?” While the homoerotic undercurrent is undeniably there, the concept is, actually, more ambiguous and rich: in the original Swan Lake, the Prince is in love with a girl turned into a white swan by an evil wizard (the girl, the white swan, and its evil/black doppelganger are all danced by the same ballerina). In the Burne's story, the Prince is in love with a swan that embodies his own idea of himself, someone he wish he could be, and the swan is, naturally, danced by a male dancer. The white swan never turns into a man (the evil/black doppelganger, the Stranger, is a man though), which makes the story resemble the one of Narcissus—if, that is, the image the doomed youth saw in the lake and fell in love with was not his true reflection but rather what he always wanted to be but could not. This subtle conceptual shift from “a boy loves a girl that turns into a swan” to “a boy loves a swan that represents his enhanced self-image” does not make this a story about bestiality nor does it detract from the tantalizing tensions of male-male pas-de-deux but it does offer an interpretation of Burne's piece as something much more nuanced than that of “a gay Swan Lake,” even though it is perfectly legitimate to read it as a metaphor of repressed and awakening sexuality, and the tragic consequences of pursuing your dream. It seems to me, however, that the tragedy of not being able to be true to himself is a broader one, encompassing a failed quest to find love, affection, and the meaning of life.

Be it as it may, one of the appealing qualities of the Burne's work is, indeed, its ambiguity and openness to a multitude of interpretations. Who is the Stranger, the villain that brings about Prince's breakdown? Is he Mr. Hyde to the White Swan's Dr. Jekyll, the dark side of Prince's personality? Where does the last act take place: in an asylum? in Prince's bedroom? in his imagination? Why do the swans turn against and murder their leader: because he wants to save the Prince even though he betrayed him with the Stranger? Or, since the Swan is Prince's self-image, is it Prince killing himself, having realized that his dream of breaking away from the life of convention and achieving freedom and love is unattainable? A lot is left to your imagination.

|

| Image: Andrea Mohin for The New York Times |

Another amazing thing that just works choreographically is a scene at a seedy bar, where number after number is danced to the Tchaikovsky music, and the fit is perfect. Who could've thought… As an aside, the music tempi are pretty fast: according to Mr. Bourne's comment at the post-performance discussion, the original Tchaikovsky's tempi have over the years become slower and slower, and he tried to restore the original speed.

It just so happened that I saw the Trocks a few days ago, and as part of their program they performed the second act of Swan Lake (!) Both troupes, I am sure, share love for classical ballet; yet, in many ways, the two companies are polar opposites: with Trocks, male dancers make fun of the ballet conventions by mastering and then exaggerating the ballerinas' techniques, dancing en pointe, wearing tutus, etc. In Bourne's production, even though there is plenty of humor elsewhere, the swan scenes are, with one exception, serious; and the dance technique is thoroughly modern.

Indeed, there is plenty of humor in the Bourne's production. He is quite clever that way: the first three scenes, The Prince's Bedroom, The Palace, and An Opera House are full of comic moments, and seeing the poor Prince endure the boring rituals of royal court creates a bond of sympathy between him and the audience, so that when the time comes for his trials and tribulations we are ready to empathize with him. Some in-jokes draw upon one's knowledge of the original ballet: as every fan of the Swan Lake knows, the Dance of the Little Swans is always preceded by the clip-clop of pointe shoes when the ballerinas run from the wings to the center stage to assume their positions before the dance starts. Bourne, hilariously, has his Little Swans deliberately stomp their bare feet for quite a while before beginning their dance! Undoubtedly, there are many funny moments that allude to the West End/Broadway shows Bourne grew up watching but I couldn't appreciate them since I don't know pop culture at all.

What I could see, however, was clever incorporation of self-referential devices, cinematographic influences, and artistic allusions. In An Opera House scene, what the audience sees at the corner of the stage is the theater box with the protagonists watching the spoof classical ballet—which takes place in its own “theater” at the center of the stage! That mock ballet, by the way, is the only instance where the classic ballet technique is used and made fun of, a-la Trocks. The nightmarish last act shows influences of Hitchcock: the shadows bring to mind Psycho, while the swans emerging from the walls and clawing their way through the pillows are reminiscent of The Birds. The final tableau of the Swan holding the young Prince in his arms high above the Queen discovering his dead body on the bed is especially poignant: the Swan's pose of Pietà, a figure of infinite sorrow and compassion cradling the dead body of the son, is a reproach to Prince's real mother whose inability to show him love and affection was one of the things that drove him to insanity and death.

So, you may ask, why should anyone see a 15-year-old production? Especially if you saw it back then or watched a 1996 DVD?

| Much has changed since then: for this run Bourne has significantly revised and tightened his choreography, toned down the comedy, beefed up dramatic tension, and de-emphasized dated references to Diana-Charles-Camilla-Fergie scandals. Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake has become a modern classic, and a whole generation of dancers grew up studying it and watching Billy Elliott. Some of them are now with the company. At the post-performance discussion, Mr. Bourne relayed that he was sent an original script for the film, and in its final scene Billy was shown in the leading role in some classical ballet. Mr. Bourne indicated that he liked the script but not the ending: since in the traditional ballet the leading males are relegated to supporting ballerinas, it was not really a very inspiring finale. Well, as we know, at the end of the film Billy is about to leap on stage as the Swan and Mr. Bourne's troupe New Adventures has acquired a permanent phantom member :) |

In the production I saw, Dominic North was Prince; and Richard Winsor, the lead Swan and the Stranger.

Continues through November 7, 2010, at New York City Center, 131 West 55th Street, (212) 581-1212, www.nycitycenter.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment