The first major exhibition in forty-five years devoted to the Burgundian Netherlandish artist Jan Gossart (ca. 1478-1532) brings together Gossart's paintings, drawings, and prints and places them in the context of the art and artists that influenced his transformation from Late Gothic Mannerism to the new Renaissance mode. Gossart was among the first northern artists to travel to Rome to make copies after antique sculpture and introduce historical and mythological subjects with erotic nude figures into the mainstream of northern painting. Most often credited with successfully assimilating Italian Renaissance style into northern European art of the early sixteenth century, he is the pivotal Old Master who changed the course of Flemish art from the Medieval craft tradition of its founder, Jan van Eyck (ca. 1380/90–1441), and charted new territory that eventually led to the great age of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640).Highlights:

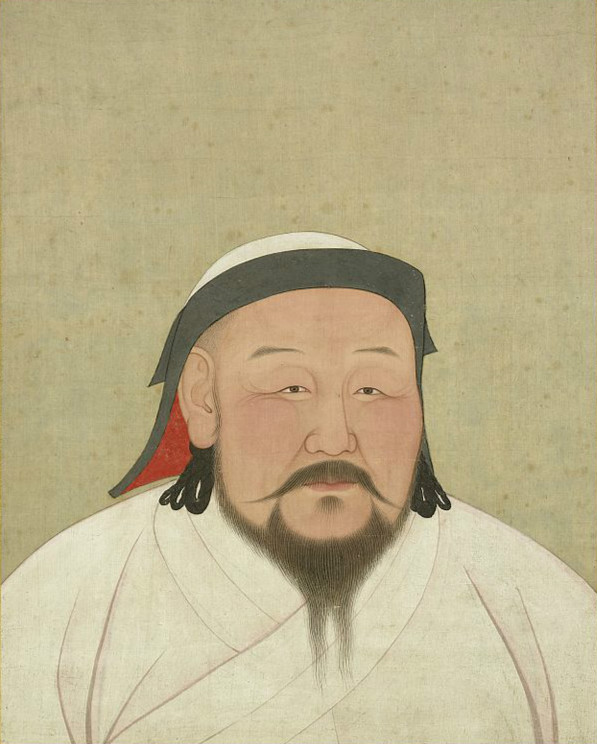

The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty

This exhibition covers the period from 1215, the year of Khubilai's birth, to 1368, the year of the fall of the Yuan dynasty in China founded by Khubilai Khan, and features every art form, including paintings, sculpture, gold and silver, textiles, ceramics, lacquer, and other decorative arts, religious and secular. The exhibition highlights new art forms and styles generated in China as a result of the unification of China under the Yuan dynasty and the massive influx of craftsmen from all over the vast Mongol Empire—with reverberations in Italian art of the fourteenth century.Interestingly enough,

When the Mongols first entered China in the early thirteenth century, Chan (Zen) was the most prominent of the several forms of Buddhism practiced in China, but under Khubilai Khan, the imperial house converted to Esoteric Buddhism, which had been brought to China by Tibetan lamas (emphasis mine—A.S.). The consequent influence of the Nepali-Tibetan (or, more broadly, Indo-Himalayan) tradition on Buddhist art at the imperial court was transformative; on view in the exhibition are several bronze sculptures that are representative of this new, hybrid style. Also on view are objects that were used during elaborate Esoteric rituals, among them painted mandalas and sculptures of terrifying protective deities. Outside the imperial court, Chan Buddhism still held sway, especially among the educated classes. Chan emphasized meditation and mindfulness in all activities as the means to achieve enlightenment. The exhibition includes paintings by and portraits of several Chan monks, including the famous Chan master Zhongfen Mingben (1263–1323). Other works on view were produced in North and South China before the Mongol conquest and reunification. These include paintings and sculptures associated with the Pure Land tradition, whose adherents were devotees of the celestial Buddha Amitabha. Also noteworthy is the imagery shared between multiple Buddhist practices, including manifestations of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin) and representations of the guardians known as arhats, or luohans.Highlights:

I may be wrong but it seems that ever since Philippe de Montebello retired, the exhibitions at the Met have become less groundbreaking.

No comments:

Post a Comment