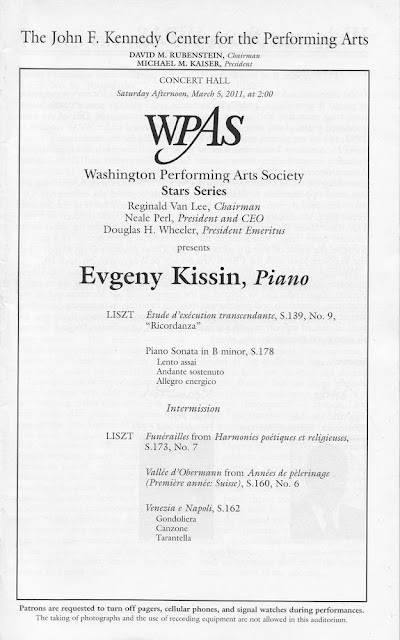

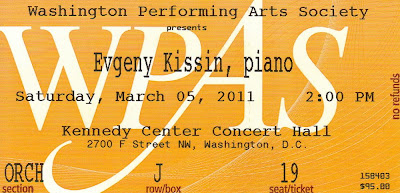

[...] in the much more rarefied playing of Kissin, presented by the Washington Performing Arts Society on Saturday afternoon in the Kennedy Center Concert Hall. The program was more limited in chronological scope, but Liszt's music sounded much more tenderly poetic, as in “Ricordanza” (the ninth Transcendental Etude), and far less saccharine. Even in “Venezia e Napoli,” Liszt's Italianate reworking of Italian composers' themes, Kissin steered clear of the potentially treacly sentimentality of this kind of paraphrase.

[...] Liszt's Piano Sonata, a work that unites many elements of his musical style: the almost keyless ambiguity of the opening theme; the metamorphosis of that theme through variation; extraordinary technical demands, and a seemingly programmatic narrative, in the manner of his tone poems for orchestra. No one knows for certain if Liszt intended the sonata to have a story, although both the Faust legend and the passion of Christ have been suggested, among many others. Kissin gave the work a driven urgency, taking no rhythmic freedom, even in the many astonishing passages in octaves, and achieving a glowing, glossy performance, alternating between sinister and angelic [...]

Kissin's pianism has an awe-inspiring fortitude: the Bellini-esque flourishes of tiny notes given a translucent, pearly sheen and the voicing of inner melodies singing clearly even when the right hand's accompanying pattern was outrageously decorated. Just as his version of the sonata told a more coherent story [...], Kissin evoked the death knell, booming drums and roaring cannon of a funeral tribute to Hungarian patriots in “Funerailles” and the restless peregrination of Senancour's hero in the “Vallee d'Obermann.” Three encores—Liszt's arrangement of Schumann's “Widmung,” the sixth movement of “Soirees de Vienne” and the famous Liebestraume No. 3—were a final reminder that Liszt was no mere showman but a sincere musician who deserves a second look.

No comments:

Post a Comment